K. Pervaiz is a queer filmmaker, born in London in the 1980s and from a Pakistani background. She grew up watching horror movies and reading gothic, horror, and classic literature. Taking inspiration from her favourite filmmakers, K describes her own work as an art form. Her filmmaking quickly became a medium for her to tell socially relevant stories, collaborate with global artists, and offer healing and transformation to herself and audiences. Since 2007, she has written and directed ten short films and two award-winning feature films, with her third feature due for release in 2026, as well as working in other uncredited production roles with her self-funded production company Bad Wolf Films. K’s feature film Black Lake, had its world premiere at the Women in Horror Film Festival in February 2020, and was nominated for 5 awards: ‘Best Director’, ‘Best Film’, ‘Best Score’ and the ‘Indie Spirit Award’, and won ‘Best Cinematography’. She completed the first cut of her debut feature film, Maya, in 2015, which after more financing and a re-edit, won ‘Best Film’ at Renegade Film Festival (formerly Women in Horror) in 2022. She was also awarded the George A Romero Fellowship for Maya at Salem Horror Fest in 2023. K returned to Black Lake in 2022 to work on a Director’s Cut before moving on to her third feature (filming from November 2023), which she screened in March 2023 as part of an extension of the Renegade Film Festival (out of competition) at the Atlanta Plaza Theatre, as a private hire. In the following interview with Amy Harris, K offers an intimate understanding of the ways she has used horror tropes to explore her multifaceted identity as a queer, British, Muslim filmmaker.

Hi K, thank you for taking the time to chat with me. I am curious about your relationship to the horror genre. Can you describe it?

K: Horror is such a wonderful blanket term to cover a range of emotions, and even as a child I knew I was different from others in my family and social groups, so horror seemed like the natural home for my curiosity about life. I found horror movies to be a great method of portraying complex personal and global issues, operating on multiple levels. For the regular moviegoer, it offers entertainment and an escape, providing short bursts of anxiety-based adrenaline, which perhaps allows for more control over real life personal narratives. For the moviegoer looking to fight their own demons, horror cinema is a mirror in which they find inner strength. That’s how the genre has transformed for me from my early childhood days of watching horror, to wanting more nuanced horror full of meaning and transformative power. Horror cinema for me has always been the conflict between the desire for death and the desire to survive, and therefore it can be very empowering seeing characters that may resonate with us, overcome all sorts of scenarios, and fighting back. I also first started reading Jung at the age of 11, so I looked for symbolism everywhere. Horror cinema is full of symbolism, far more than any other genre in my opinion! Now that I’m entering a calmer phase of my life and working through what Jung calls the process of Individuation, I find myself drawn to global stories with elements of horror, rather than things that fit neatly within the horror genre.

The democratisation of film, such as the easy access to cheap equipment and independent distribution channels, has enabled more people to make horror films in the UK. Although there are more opportunities and new avenues of filmmaking and distribution, there are still barriers to independent filmmaking. What barriers have you had to overcome?

K: Financing has always been a huge concern. It’s the main thing that has stopped me from producing films within a two-year time frame. My feature films end up taking 3-5 years from script to post-production because I work a full-time job. I take time off work to film, and I travel to find surreal and wonderful locations to bring to the screen, but it’s mentally exhausting. I sit with these heavy ideas in my mind for years, and they’re just waiting to be brought to life and experienced. The most difficult aspect is not having a place of my own and having to compromise my living space at times to create my work. It has often felt like a choice – I either pay rent, sacrifice the things I do for my wellbeing, and spend 10 years making a movie, or make compromises to make my films in 5 years whilst also being able to travel and take care of my wellbeing. Also because of the peculiar nature of my filmmaking techniques, I rely on private investment as I don’t qualify for public funding as I often operate with a skeleton crew. As a filmmaker, this has allowed me to reflect a lot during those large pockets of spaces between the different stages of production, which is perhaps why the art itself I think takes on a meditative quality.

The experiences you describe pertain to a broader precarity within the film industry, particularly for those from global majority backgrounds. Your oeuvre demonstrates how specific economic environments can affect filmmaking. What advice would you give your past self, regarding filmmaking?

K: Regarding film festivals, I would tell myself to never rush stages of filmmaking to meet film festival deadlines. To take my time even if it means submitting the following year. I would tell myself to be selective and research the audience, the festival, and festival director’s ethics, to make sure they align with my own as this will also save me a lot of time, energy, money and allow me to value my work more. Regarding film production, I’d tell myself to be confident and brave enough to immediately let go of anything that doesn’t serve the vision for my film, because time is money and it’s my money, and to trust the supernatural unfolding of the journey ahead.

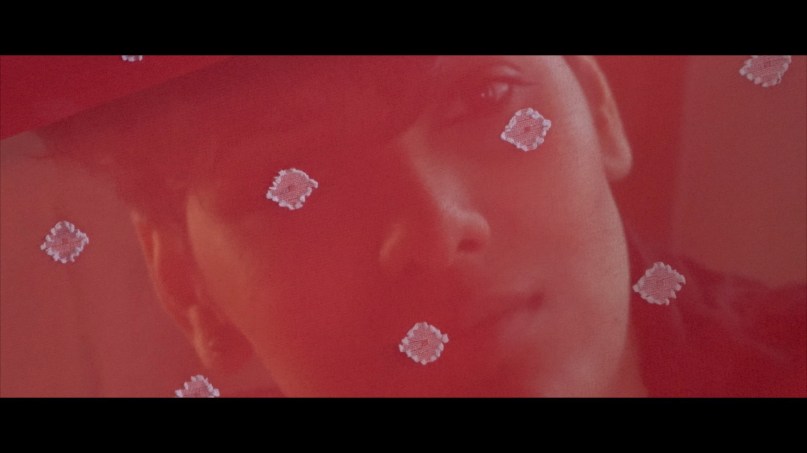

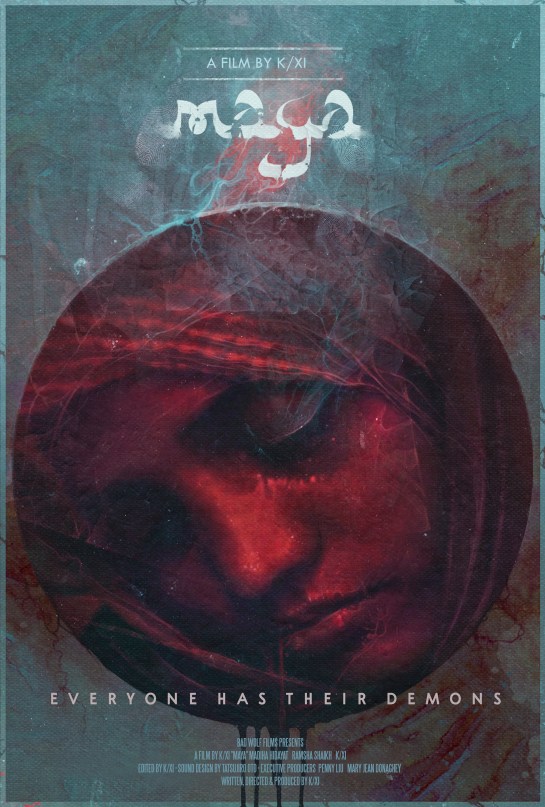

We have discussed before how you have used limited funding and distribution opportunities to explore the genre in distinctive ways, using film to explore culturally specific themes relating to your own identity. I like to think that your films can be understood as facets of your identity: Black Lake (2020) considers intersections of British and South-Asian cultures through the folklore of the churail, a vengeful female spirit in South Asian mythology; Maya (2022) unpacks cultural trauma and Jinn possession; Vessel (currently in production) navigates sexuality and violence against women in Pakistan using black magic. Can you speak to how your identity has changed and morphed with each production?

K: I’ve realised for me personally over the past 5 years, that my art/films are part of my spirituality, so each project is no longer about the finished piece of art, but the entire journey. I make the movie; the movie makes me. We work together to create a vision, and throughout this lengthy process I die a few times, and a new version of me is birthed. It’s incredibly intense. Each film is an analysis and reflection of a part of my life, offering catharsis, healing, and growth. I’m understanding now that that was always the goal. It really does feel like an expensive form of therapy, but I get to witness my unravelling and becoming on a screen, as if it were a mirror or a portal. Because the process of making the films were often longer than anticipated, I’m now recognising that I must revisit the original ideas/script during the time between writing and filming, so when I finally get behind the camera, that script reflects the person I am at that moment and not one to three years prior. This is something I’m focusing on with my third film to avoid having to revisit it like I did with my first two feature films. I’m definitely more self-aware now and confident about who I am both as a person and as an artist, and this process has sharpened my intuition too. I’ve learned since my last film, to better communicate what I want, and when it’s difficult to communicate certain ideas, I trust myself to choose to work with the right people who know to just trust my intuition because that’s the kind of person I am. I feel very connected.

In line with our other collaborative publications, this interview shows that the post-2000 British horror boom has created spaces for diverse voices to be heard for the first time. However, media, academic circles, and industry figures often fail to recognise micro-budget, small studio production and distribution as a valid area of filmmaking means that, with very few exceptions, a lot of independent horror has been overlooked, despite its undeniable commercial appeal. How can you carve out an identity as a filmmaker in such a saturated market?

K: It’s really disheartening to see so many filmmakers being exploited. Very rarely do low-budget films make any money at all even when being streamed on mainstream platforms. I think the most important thing is to understand why one wants to make films. For me, it’s something that I must do. It’s who I am. As long as we are able to clear a path for our voices to be heard and understand that we each have something unique to offer, then we must. The film industry is changing constantly so it can be difficult to predict what can happen once a movie has been made, which is why I focus on telling a story rather than being goal oriented in terms of having my film being distributed widely and gaining financial success. The reward for me is the personal responses I receive from audiences at film festivals about how my films have affected them. People feel seen and heard, and that’s a very rare and beautiful thing.

Your passion for your craft is unwavering! Thank you again for sharing such personal insights into your films and filmmaking process. As a final question, where will your journey as filmmaker take you next?

K: I am currently working on my third feature film Vessel and in the process of sourcing investment for the main shoot in 2025. Meanwhile, I have self-financed equipment upgrades and re-written parts of the 2021 script this summer. I have already filmed a couple of scenes in Pakistan and will be filming in Greece and Turkey later this year to continue building up shots of landscapes and other elements of the story. The aim is to have the film completed by summer 2026. During this time, I also plan on releasing a limited number of physical copies of both Maya and Black Lake: Director’s Cut.

K Pervaiz is a filmmaker & independent scholar. She has written and directed ten short films and two award-winning feature films, with her third feature Vessel due for release in 2026. K also runs her own production company Bad Wolf Films.

Amy Harris is a fully funded PhD student in the Cinema and Television History Institute at De Montfort University, writing her thesis on contemporary women directed horror. Her research expertise is in British horror and cultural history, focusing upon intersecting representations of gender, class, and race.