By Peter Krämer

I have to start with an admission: I was very much prepared to enjoy and celebrate the second sequel to Danny Boyle’s by now classic horror movie 28 Days Later (2002), in particular the performance of Jodie Comer who received top billing for the film; but I was deeply disappointed when I recently saw 28 Years Later during the first weekend of its release (20-22 June 2025). The disappointment has a lot to do with Comer’s brilliant career leading up to this film (about which more later) and the fact that the character she plays here was written by the British novelist, scriptwriter and film director Alex Garland.

I think I am not the only one who loved much of Garland’s work, and especially some of the female characters he created and the film performances they gave rise to, without even being aware of his name. When about two years ago my friend and academic co-conspirator Stevie Simkin told me about his interest in Garland, I first responded with ‘Alex who?’ and ‘Isn’t that the guy who wrote The Beach?’ (referring to the 1996 novel about an alternative community of Westerners on an exotic island which was filmed by Danny Boyle in 2000).

I then checked Garland’s Wikipedia entry and immediately realised why film scholars such as Stevie and myself should be interested in Garland’s work. Unbeknownst to me, several of my favourite films of recent years, notably the Science Fiction movies Never Let Me Go (2010), Ex Machina (2014) and Annihilation (2018), were based on Garland’s scripts and the last two he had also directed.

I quickly watched and re-watched all the films and also a television series that Garland had been involved with (as a writer, director and/or producer),[1] read his three novels, re-read the novels Never Let Me Go (2005) by Japanese-British author Kazuo Ishiguro and Annihilation (2014) by the American writer Jeff VanderMeer, and also finally saw the adaptation of The Beach (in which Garland was not involved). It was a truly eye-opening, or should this be ‘mind-opening’, experience.

As Stevie pointed out to me, it is striking how much of Garland’s work centres on female characters, including Never Let Me Go, Annihilation, the horror drama Men (2022), the near-future combat movie Civil War (2024) as well as the Science Fiction television series Devs (2020) and two of the storylines in his second novel The Tesseract (1998; a film adaptation, which he was not involved with, was released in 2003). Even if women are not at the centre of the stories, Garland’s work foregrounds compelling and in some cases exceptionally forceful female characters in, for example, 28 Days Later, the Science Fiction films Sunshine (2007) and Dredd (2012), all of which he scripted but did not direct,[2] as well as Ex Machina.

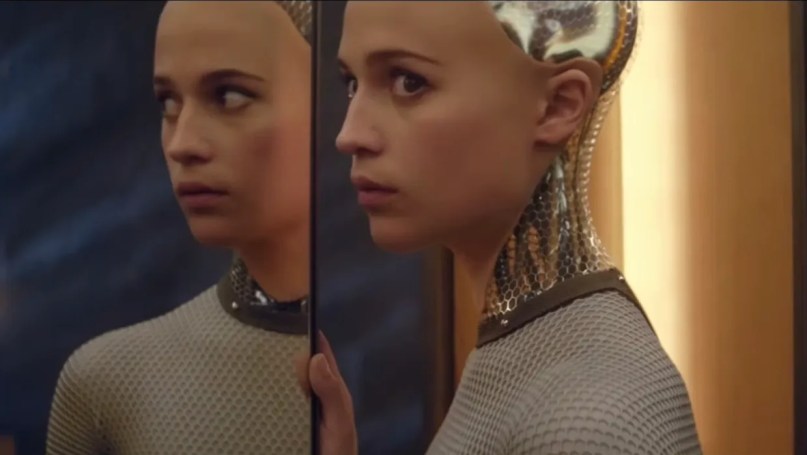

The female characters Garland created in his novels and in his original scripts were the basis of powerful film performances by a host of female (often British) actors such as Tilda Swinton (in The Beach), Saskia Reeves (in The Tesseract), Naomi Harris (in 28 Days Later), Rose Byrne and Michelle Yeoh (in Sunshine), Alicia Vikander (in Ex Machina), Jessie Buckley (in Men) as well as Kirsten Dunst and Cailee Spaeny (in Civil War).

The novels Garland chose to adapt (in the case of Annihilation it was a very loose adaptation indeed) gave rise to a particularly rich panoply of female performances, by Carey Mulligan, Keira Knightley, Sally Hawkins and Charlotte Rampling (in Never Let Me Go; all of them British) as well as Natalie Portman, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Gina Rodriguez, Tessa Thompson and Tuva Novotny (in Annihilation). In his adaptation of the British Judge Dredd comic, Garland chose to foreground two female characters, who were then played by Olivia Thirlby and Lena Headey. Last but not least, Garland cast Sonoya Mizuno in all the films he both wrote and directed[3] – Ex Machina, Annihilation, Men and Civil War – and gave her the lead in Devs, which he also wrote and directed.

Garland’s novels, the novels he chose to adapt and his original scripts often, but not always, feature at least some British characters. On screen they are usually played by British (or Irish) actors; and those actors also play characters of other nationalities in the films Garland is associated with. Although it is difficult to determine whether he had any influence on the casting of the films he did not direct himself, I suspect that, as the film’s executive producer, he may have had a hand in giving the role of the incredibly gruesome (and previously horrendously victimised) villain Ma-Ma in Dredd to British actor Lena Headey.

His casting decisions for his directorial debut Ex Machina are of particular interest. This is a largely British production telling a story set in the United States with presumably American characters (as signalled by their accents), yet one of the two male leads is played by an Irish actor (Domhnall Gleeson), and the main female-coded humanoid robots are played by a Swede (Vikander), a Japanese born Brit (Mizuno, in only her second ever on-screen appearance, the first one having been very minor indeed) and a Mongolian woman (Gana Bayarsaikhan in her screen debut).[4] Bayarsaikhan was launched on a somewhat uneven, and yet for a Mongolian actress perhaps uniquely successful, career in American and British film and television.

Mizuno followed Ex Machina with both minor and major roles in an impressive number of movies and television series. Except for the lead of Devs, Garland cast her only in supporting roles, but she had more central, including some (co-)lead, roles in the work of other filmmakers, for example in the post-apocalyptic horror movie The Domestics (2018), the psychological Science Fiction series Maniac (2018) and the comedy-drama Am I Ok? (2022), also as a voice actor in the animated series Terminator Zero (2024).

Vikander had been a well-established film and television actress in Sweden, with a couple of minor roles in English language productions in 2012/13, before she achieved international stardom with lead roles in four English language films in 2014, the second of which was Ex Machina. Ever since, Vikander has been closely (but by no means exclusively) associated with British filmmakers and British source material, appearing in a wide range of British and Hollywood productions, playing characters of many nationalities.

Perhaps it is appropriate to say that – especially as Vera Brittain (in Testament of Youth [2014]), Lara Croft (in Tomb Raider [2018]) and Catherine Parr, the last wife of Henry VIII (in Firebrand[2023]) – she has become a staple of British cinema and indeed British culture. Her appearance, in the same year, in Testament of Youth and Ex Machina helped to make this possible.

For his second film as a director, Annihilation, Garland had a much bigger budget than for Ex Machina and tried to play it safe by employing a number of highly experienced and mostly well-known actors for the female roles, including a bona fide (and also highly critically acclaimed) movie star (Natalie Portman). The situation was similar for his fourth feature, Civil War, with another comparatively big budget and another critically acclaimed movie star (Kirsten Dunst).

Interestingly, though, he gave the second female lead role to relative newcomer Cailee Spaeny, who had only very recently embarked on a movie career (with a few supporting roles) when Garland first cast her in an important supporting role (as a male character) in Devs. By the time Civil War came out she had been establishing herself as a Hollywood leading lady in films ranging from The Craft: Legacy (2020) to Priscilla (2023) and Alien: Romulus (2024). Arguably, Garland’s casting decisions have been quite important for Spaeny’s rise to stardom.

For his third film as a director, Garland chose a fairly low-budget British production. Men is essentially a two-actors piece, whereby Rory Kinnear plays a range of male characters and Jessie Buckley the female lead (other actors make only minimal appearances in the film). Born and raised in Ireland, Buckley attended both the Royal Irish Academy of Music and RADA in London. By the time she appeared in Men, Buckley had established herself as a highly acclaimed actress on stage and screen and as a singer. From 2018 onwards she has been nominated for (and regularly won) film, television and theatre awards, including some recognition for her performance in Men, but unlike several of the other female actors mentioned earlier, being cast in a Garland project did not give her career a particular boost.

Perhaps Men is simply too weird for giving anyone a career boost. One way of re-telling its story would be to say that a woman traumatised by her husband’s suicide (and the emotional and physical bullying that preceded it) rents a country house for her holiday. The behaviour of the men she encounters in and around the house (all played by the same actor) turns increasingly transgressive and threatening. Extreme violence ensues, replaying certain aspects of her husband’s suicide and culminating in an extraordinary birthing sequence in which a man’s body emerges from another man’s body, over and over again, until finally her late husband sits opposite her.

Given the fantastic nature of the events in and around the country house, one has to doubt that they really happen; they might only occur in the woman’s mind. And the same conceivably applies to flashbacks to her relationship with her husband and his suicide. One gets the impression that there is simply no baseline reality at all; it is all fantasy, all merely happening in someone’s head (which is also precisely the situation in Garland’s second novel The Coma [2004], here with a male protagonist, if that’s what he really is). One is tempted to say that the film is not necessarily the fantasy of the female character played by Jessie Buckley but, more straightforwardly and self-consciously, the fantasy of writer-director Alex Garland.[5]

Perhaps this is not altogether different from the first script Garland wrote for himself to direct. A young programmer (Caleb) is brought to the isolated home of the CEO (Nathan) of the tech company he works for so as to run tests on a humanoid robot named Ava. Unbeknownst to Caleb, he is in fact the test subject: will he develop deep feelings for Ava, who has a clearly robotic body with some attractive female/feminine features? Nathan orchestrates all this, but eventually loses control when Caleb, who has indeed developed feelings for Ava, sets ‘her’ free and ‘she’ then kills Nathan and escapes from his home, leaving Caleb locked in (presumably to die a miserable death). Hiding their robotic features, Ava joins the world of humans.

One could see this as a kind of twisted allegory of the filmmaking process itself, with Nathan, as the orchestrator, standing in for writer-director Garland and the characters of Caleb and Ava serving as performers in his ‘play’. Except that this time the story culminates precisely in the female-coded performer escaping from the play imposed on them, entering a (story)world beyond the control of Nathan, and also of Garland: there is no indication that the writer-director has any idea about what Ava might do next (it could well involve reshaping the world known to humans/men).

There are similar allegorical dimensions and surprising twists to do with male controllers/creators and a female protagonist in Devs, but they are very difficult to summarise. Let’s just say that the series revolves around a machine (referred to as Devs which is eventually revealed as the Latin spelling of Deus/God), mostly built by men who are led by yet another tech CEO, and able to generate a perfect digital recreation of the past as well as a perfect digital prediction of the future. Most people involved in this supersecret project assume that the workings of the machine prove that our world is fully deterministic: all human actions are pre-determined, there is no such thing as free will. But the series’ female protagonist Lily (an echo of the mythical Lilith?) departs from Deus’s predictions, and thus makes possible the creation of whole new worlds which are overseen by two female characters.

Another tech CEO standing in for writer-director Alex Garland, another female(-coded) character refusing to play the game laid out for them, and once again a world, or worlds, becoming possible in which men are no longer in control. I guess it would be interesting to find out whether, during the making of the films he directs, Garland insists on full control of every detail or whether there is instead some leeway for female performers to take their performances and characters in unexpected directions; also whether they or he have any concrete ideas about where the stories might go after the final scenes.

I should add that Annihilation culminates in a scene in which the body and mind of the female protagonist has, apparently, been transformed by an alien force so that she is now no longer (fully) human and perhaps beyond human understanding. In fact, together with ‘her’ equally transformed husband, ‘she’ may constitute an alien vanguard for transforming the human world.

And in Civil War, the film’s imagery is intermittently controlled by the two female war photographers whose images interrupt the flow of moving pictures. Being heavily invested in, among other things, writing (and sometimes directing) extremely violent films, with plenty of fighting and damage to the human body, Garland is, to some extent, reflected in the war photographers who somewhat obsessively aim to capture combat, destruction and death. At the end of the film, Garland focuses on the Cailee Spaney character taking pictures, and the credit sequence shows what is presumably one of the photographs she took being developed. In a sense the male director hands the ending over to the female photographer.

So far, so very good, I thought. And then came Warfare (released in April 2025), a film Garland co-wrote and co-directed with former Navy SEAL Ray Mendoza, who had been his military adviser on Civil War. Meticulously reconstructing a specific event during the Iraq war, this is an almost exclusively male affair, with women having hardly any screen time at all although some are present both in the house which a Navy SEAL platoon takes over and in the streets outside. One wonders what the experience of the Iraqis trapped in their own house was like, but the film shows no interest in this.

While I was surprised by the radical marginalisation of women in Warfare, I was willing to accept it as an integral aspect of the film’s generic focus on male combat. But, surely, I thought, with 28 Years Later Garland (as scriptwriter) would return to his previous emphasis on female characters, especially when I learned that Jodie Comer would play the lead (which, of course, turned out to be a bit of misinformation).

Comer had worked mainly in British television for over decade, most famously in the spy drama Killing Eve (2018-22), before becoming a movie star. Following on from two small roles in earlier theatrical movies, in 2021 Comer received second billing for the action comedy Free Guy and third billing for the historical drama The Last Duel, which was followed by her second billing for the sixties drama The Bikeriders and top billing for the ecological disaster movie The End We Start From (2023). In the latter she plays a mother trying to survive, and to protect her child, in a chaotic world (more specifically an England devastated by floods), which seemed to be a kind of rehearsal for her role in 28 Years Later.[6]

The earlier two films in the series centrally focus on the experiences and actions of male characters, but also prominently feature female characters whose actions move the story forward while, among other things, they competently defend themselves (and others) against the infected. Both films conclude with a focus on a small group of male and female survivors.

28 Years Later is more narrowly focused on a male protagonist (whose most formidable infected opponents and uninfected allies are also all male) and gives much less screen time to female characters. The protagonist is a boy undergoing a rite of passage (or, rather, several such rites), and it is only through his perceptions and actions that sustained attention is drawn to a female character (his mother, played by Comer). This character is oddly passive most of the time, with the notable exception of once, in a dream-like scene, defending her son and of helping an infected woman to give birth.

As it turns out she suffers from cancer which has strongly affected both her body and her mental capacities, and she eventually appears to agree to a mercy killing (by a male doctor). Before a rather disruptive final scene setting up the next film in the series, the boy is shown roaming the landscape all on his own.

Early indications are that the cast and story of 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple, which has already been shot and will be released in January 2026, is equally male dominated. Whatever else one may say about these latest instalments in the series and about Warfare, as an admirer not only of Garland’s work in general but also of the female (or female-identified) characters he creates in particular, I find the marginalisation of women in his stories after Civil War deeply regrettable. But there is perhaps some comfort in at least imagining the film that 28 Years Later could have been had it focused on the story of the mother, who, in my view, is by far the most interesting and, not least through Comer’s performance, by far its most engaging and compelling character.

Peter Krämer is a Senior Research Fellow in Cinema & TV in the Leicester Media School at De Montfort University (Leicester, UK). He also is an Honorary Fellow in the School of Media, Language and Communication Studies at the University of East Anglia (Norwich, UK) and a regular guest lecturer at several other universities in the UK, Germany and the Czech Republic. He is the author or editor of twelve academic books, including American Graffiti: George Lucas, the New Hollywood and the Baby Boom Generation (Routledge, 2023). For many years he has published about, and taught courses on, the role of women in Hollywood (both on and off screen).

[1] It seems that Garland was only marginally involved in 28 Weeks Later (2007), the first sequel to 28 Days Later, which is why I am going to ignore the film in this piece. The same applies to the action movie Big Game (2014). For both of these films, Garland did receive an executive producer credit but it is not at all clear to me whether he actually helped shape these films.

[2] While Danny Boyle directed Sunshine, it seems that Garland did have an uncredited part in directing Dredd.

[3] Mizuno is not in Warfare (2025), which Garland co-wrote and co-directed.

[4] It may also be worth taking a closer look at the other actors Garland cast as female-coded robots (usually in their feature debuts), notably the Estonian Elina Alimas and the Black British Symara Templeman.

[5] In fact, I suspect that Garland’s casting of Buckley in Men had something to do with her appearance in Charlie Kaufman’s mind-bending psychological drama I’m Thinking of Ending Things (2020), which, like Men, focuses on a woman’s subjectivity and her experience of a confusing and in places rather threatening world, whereby, in a final twist, the whole story appears to arise from, or be located within, an elderly man’s consciousness.

[6] Comer also had great success with the one-woman play Prima Facie in the West End and on Broadway in 2022/23.